On a Personal Note

Okay, this is a disaster. I wanted to send out this E-Mail hours ago; however, I got sucked into various rabbit holes while putting everything together. So, here we are 😭

Now, I lack the time and energy to write a good intro. Luckily, this ain’t needed as I assembled some bangers this week. Although I already need to warn you about the fact that I went rogue on the second piece; but I was in my WWE era and simply couldn’t help it. You will see.

Having said that, this might be the right time to ask for your support: Make your friends and family subscribe. Because I really need more than the usual five people who like my niche memes… (jk, don’t make anyone subscribe to any of this lol)

Russian Exceptionalism

Towards the end of last year, I gave two lectures on Russian political philosophy and Eurasianism (unfortunately they are only available in German). Shoutout to Alex who threw me (most lovingly) under the bus here—as I not only had to cover two insanely vast subjects in a very short time; but I also needed to extract a somewhat interesting argument while not losing all nuance. For example, it would have been easy to claim that Russian thinking is just different. Case closed. However, that is simply not true. As we all know, Russia has been the biggest playground for the ideas of German philosophers, such as Hegel or Marx—with a unique Russian spin. And that was what my lectures were about. In essence, I wanted to show that the common sentiment of Russian exceptionalism, i.e. that Russia can only be understood by Russians (“Умом Россию не понять” or Dostoyevky’s famous “Russian Soul”), is just false. A sociopolitical adaptation of Hegel ain’t no rocket science, one must say. Especially if you consider that Russian political history is mostly shaped by three major factors: the ‘republican’ tradition of local governance (вече/земство), the Byzantine heritage of Orthodox Christianity, and the Tatar legacy of a centralized state. (If you want to dig deeper into this, I highly recommend Evert van der Zweerde’s excellent book on Russian Political Philosophy). In any case, here is now a shorter piece that will tie together many of the themes that I have covered over the last couple of years—from Berdyaev to Savitsky and Trubetskoy to Gumilev. In fact, it resembles my writings and talks so closely that it is almost uncanny. You will see.

Unfortunately, all of this feels relevant in a week where Putin got another center stage for his bogus alternative history. I hope that we are now finally done with the Mearsheimer crowd. Putin couldn’t have been more clear that it wasn’t shallow IR theory that explains his actions…but Yaroslav the Wise :(

When Russian troops seized Crimea in 2014, German chancellor Angela Merkel, reporting on her conversation with Vladimir Putin, told President Obama that the Russian president seemed to dwell “in another world.” In a sense she was right: Russians and Westerners see the world quite differently, and our failure to understand Russia’s perspective made its actions seem surprising in 2014 and still more so when it invaded Ukraine in 2022.

How do Russians think about what their country is doing in Ukraine? If we are to grasp why so many have supported the attack on Georgia in 2008, the seizure of Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2014, and the present war, we need to recognize that their fundamental assumptions differ from ours. Americans, for example, typically take for granted that the state exists to promote the welfare of its citizens, but Russians often believe the opposite. After all, individuals come and go, but Russia remains. And Russia is not just a nation; it is also an idea.

The “Russian idea,” throughout its many changes, has typically been messianic. It explains the world and gives life purpose; it shapes domestic and foreign policy and, more importantly, gives Russians a sense of their “Russianness”—which includes the ability to save the world. In his famous book The Russian Idea (1946), the philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev argued that Bolshevism owes as much to Russian messianism as to Marx. Medieval Russians, he and many others emphasize, often considered themselves the only true Christians. The Byzantines had, at the Council of Florence in 1439, recognized the pope to secure Western aid against the Turks, thereby betraying the Orthodox faith, which is supposedly why they succumbed to the Ottomans in 1453. From that point on, Moscow, the capital of the only independent Orthodox country until the nineteenth century, became the “Third Rome,” the heir to both Rome and Byzantium as the seat of Christendom. Russians were destined to save the world because, as the monk Philotheus explained, “a fourth Rome there will not be.”

[…]

After the fall of the USSR, ideologies competed to replace communism. Liberalism, considered foreign, was overwhelmed by various types of nationalism, one of which, Eurasianism, seems to have achieved the status of a semiofficial ideology. Putin uses Eurasianist phrases, the army’s general staff academy assigns a Eurasianist textbook, and popular culture has embraced its ideas and vocabulary. The better to build an empire, Eurasianism, like Stalinism, carries the banner of anti-imperialism, claiming to unite the world under Russian leadership in order to liberate it from Western cultural colonialism. It could be no other way. As Aleksandr Dugin, the movement’s current leader, explained, “Outside of empire, Russians lose their identity and disappear as a nation.”

[…]

During the Yeltsin years, which many called Russia’s “Weimar Era,” the young, bohemian Aleksandr Dugin flirted with occultist and extreme rightist ideas. He seems to have been especially fond of Nazis and adopted the nom de plume Hans Sievers, an allusion to Wolfram Sievers, whom Himmler made director of a group studying the paranormal. Eventually Dugin found his way to Eurasianism, which he synthesized with the work of practitioners of geopolitics from Halford Mackinder on, along with structuralists, postmodernists (Jean-François Lyotard, Gilles Deleuze), French “traditionalists” (René Guénon and Alain de Benoist), and various Nazis or ex-Nazis, including Julius Evola, Carl Schmitt, and, of course, Martin Heidegger.

It is routine to refer to Dugin as “well-read,” but it would be more accurate to say “well-skimmed.” He is one of those pseudoprofound commentators who love to call things “ontological” and “metaphysical” while endlessly dropping the names of thinkers, with many of whom he has a flyleaf acquaintance. If there are fashionable terms to deploy—“rhizome,” “bricolage,” “Dasein”—he is sure to pile them one on another. He speaks of the “hermeneutic circle”—the paradox that we interpret a whole work in reference to the parts and the parts in reference to the whole—as if it meant a worldview. He baffles with what might be called the emperor’s new prose:

The new age of modernity, with its linear vectors of progress and with its postmodern contortions,…are taking us away into the labyrinths of the disintegration of individual reality and to the rhizomatic subject or post-subject.

Real, if wacko, thinkers like Trubetskoy, who identified the phoneme and helped found structuralism, and Gumilev, who was a genuine scholar of the Mongols and peoples of Central Asia, would probably be embarrassed that Dugin is their successor.

Dugin’s most influential book, The Foundations of Geopolitics, began as a lecture series at the General Staff Academy and continues to be assigned at military universities. As the historian John Dunlop observed, “There has probably not been another book published in Russia during the post-Communist period which has exerted a comparable influence on Russian military, police, and statist foreign policy elites.” And not just elites: Dugin’s ideas—cited, recycled, adapted, and plagiarized—fill bookstores and saturate mass media. In the late 1990s the Duma formed a geopolitics committee, and Dugin became an adviser to the Duma’s speaker, Gennady Seleznev.

Dugin stresses Eurasianism’s apocalyptic element. Russians face a final battle of good and evil, a “cultural, philosophical, ontological, and eschatological struggle.” Evil is variously identified as Atlanticism (opposed to Eurasianism “in everything”), modernity (“an absolute evil”), America (“a country of absolute evil”), and above all liberalism, which he says is powerful today because evil is strongest at the end of days. Gumilev imagined he was doing science, but Dugin expresses animus toward “materialistic physics,” Francis Bacon, and “the supremacy of quantitative concepts and secular theories.” In his introduction to Eurasian Mission he also rejects “homogenous space,” “linear time,” and “progress.”

[…]

In Dugin’s view, Eurasianism, suitably adapted, provides the best ideology of resistance to liberalism. Russia must lead not only other steppe peoples but everyone oppressed by the West; in this sense, Eurasia is everywhere. Dugin calls this updated Eurasianism “the fourth political theory,” which he elaborates in his book of that name. Totally rejecting the first theory, liberalism, Eurasianism borrows generously from the other two, communism and fascism. Like Lenin and Stalin, Dugin advocates using any means whatsoever in the struggle against “blood-sucking American, oligarchic, liberal scum.” And we must get over making Hitler into a bogeyman, because apart from its antisemitism, Nazism was no worse, and maybe better, than liberalism.

Like earlier Eurasianists, Dugin argues that all cultures are equal and incommensurable, but he makes an exception for Americans, who possess no “deep identity” because they lack “a pre-modern legacy.” With similar disregard for contradiction, Dugin demands that no country should dominate others while arguing that Russia must wield total power in the fight against America. If Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan don’t want to be united with Russia, that is only “to exploit their recently achieved national sovereignty for their own gain”—which, one might think, is what nations are supposed to do.

Dugin expresses special hostility to independent Ukraine because, despite its cultural and linguistic closeness to Russia, it has treasonously betrayed its proper role as part of the Russian world. In 2014 he called for the conquest of eastern Ukraine months before it happened and even revived the eighteenth-century term for the region, Novorossiya, before the Kremlin started using it. He told one reporter, “Kill! Kill! Kill! There can be no other discussion.” He now demands that Putin wage war more ruthlessly.

Far from distorting earlier Eurasianism, Dugin’s bloodthirstiness represents its predictable development. As has happened so often in its history, Russia demonstrates the consequence of defining oneself with an idea. In the name of justice, one creates an ideocracy and divides the world into absolute good and evil. Immediate neighbors suffer first.

To an extent Westerners have not appreciated, concern with national identity has shaped Russia’s foreign policy over the past decade and accounts for the dramatic shift in its behavior from peaceful concern with economic development to aggressive efforts to dominate its neighbors. Since Putin resumed the presidency in 2012, Eurasianist vocabulary has populated his speeches, newspaper articles, and television appearances. Russia’s elites have embraced Eurasianist concepts defining Russia as a distinct “civilization.” The West has become the liberal “Atlantic” intent on destroying Russian culture, while Russian patriotism is now a matter of “passionarity.”

[…]

Time and again, Putin has stressed that Eurasian cultures belong together in a single polity under Russian leadership. He has regarded his new “Eurasian Union” with Kazakhstan not just as a trade agreement but also, and more importantly, as the union of peoples who belong together as a single “civilization.” The identity of that civilization, he explained, is based not on ethnicity but on culture—“on the preservation of the Russian cultural dominance, the carriers of which are not only ethnic Russian, but all carriers of such identity regardless of Russian nationality.” This concept of a broader civilizational identity that transcends nationality but still entails Russian dominance is a core idea of Eurasianism.

More often than not, Putin has defined Eurasian civilization negatively, as the opposite of decadent liberalism. In a 2019 interview with the Financial Times, he explained that “the liberal idea” had “outlived its purpose” and “become obsolete.” But it is still dangerous because Western leaders presume that their values are the only rational ones. Expanding NATO to the Russian border and seeking to incorporate traditionally Russian territory, they equate their interests with humanity’s and take for granted that they can “simply dictate anything to anyone just like they have been attempting to do over the recent decades.” On May 9, 2023—Russia’s most important holiday, celebrating the defeat of Nazi Germany—Putin appealed to Russian patriotism in its current fight against liberalism and the West in Ukraine. The West hates Russia, he said, precisely because it represents different civilizational values. “Western globalist elites,” Putin insisted, resent having their supposedly universal values challenged and in response have provoked “bloody conflicts, hatred, Russophobia.”

In 2016 Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, in an article citing Gumilev, claimed Russia’s actions in Ukraine were about resisting Western attempts “to deprive Russian lands of their identity.” Contrary to the worldview Merkel and other enlightened Westerners take for granted, existential civilizational conflict, from the Eurasianist perspective, is regarded as inevitable. In that conflict, Russia is the victim of arrogant Westerners seeking to impose their alien, “satanic” values on the rest of humanity. Its struggle, in this view, is not about conquest but the preservation of its very identity. Ultimately, it is also the fight of all non-Western powers who want to maintain their own distinct civilizations. “We will protect the diversity of the world,” Putin explained in a tone that demonstrates that, now as in the remote past, Russian messianism still thrives.

The New Authoritarian Personality

For over a year, I was facing this harsh dilemma: I desperately wanted to take down this grotesquely bad and potentially malevolent pseudo-academic book called “Gekränkte Freiheit” (“Hurt Liberty” or sth like that); but it was only available in German. So, I couldn’t share this treasure trove of politically motivated pseudo-science here. Now, the authors finally dared to publish an English piece about this garbage that they call “sociological research.”

As you can see, I’m uncharacteristically brazen here. Usually, I take all sorts of arguments seriously. FFS, I even gave Bronze Age Pervert a charitable reading just last week. Yet, the difference is that BAP neither misrepresents the ideas of the other camp (i.e. liberalism) nor hides behind the guise of academic research. These two German academics do both: They turn established concepts (e.g. liberalism, authoritarianism, etc.) around and deplete them of their original meaning just to construct an argument that aims to toxify concepts and smear movements that they politically oppose. Of course, this ain’t something new: This is a common strategy that we all know from the likes of Vladimir Putin or Viktor Orban. Unlike them, however, their sweeping conclusion that people who love liberty turned authoritarian is based on a stunning set of sixty (!!!) interviews on matters of critical theory. And “No!”, I am not kidding. Obviously, the German feuilleton and pseudo-intellectuals ate that garbage up like candy. Okay, I will stop with my rant now. Apologies. You can check out this stuff for yourself and tell me whether this makes any sense…it doesn’t, so I kept some commentary for the lulz. Enjoy:

The political success of libertarians is arguably the most astonishing phenomenon of these strange times. They traditionally privilege individual freedom over, and at the expense of, collective freedom. But another emerging characteristic, one also shared by its most prominent adherents – such as Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and the anarcho-capitalist and Argentine president-elect Javier Milei – is that their libertarianism is infused with authoritarian tendencies. [SG: Again, this sounds like an interesting research question. I give you that.]

Like neoliberals [SG: You know it will get bad when this is your first sentence], libertarians are sceptical of the democratic state, not as a threat to smoothly functioning markets, but as a machine that restricts individual freedoms. [SG: Bruv, all liberals from Tocqueville to Mill have been concerned with balance of democracy and rights] Neoliberals use the state to strengthen the market, whereas libertarians consider the state itself, the authorities and their regulations, to be invasive and harmful. They also mobilise against multiculturalism and what they perceive to be enforced solidarity with vulnerable groups, such as asylum seekers or minority groups, and many were vehemently opposed to the lockdowns and other biomedical requirements, such as mask-wearing, during the Covid-19 pandemic. [SG: Here you can see how disingenuous this argumentation is: Oh, libertarians are skeptical about the state. Conclusion: They hate asylum seekers. WTF?]

[…]

In the preface to The Authoritarian Personality (1950), the Marxist critical theorist Max Horkheimer spoke of “the rise of an ‘anthropological’ species we call the authoritarian type of man”. This person combined rationalism and anti-rationalism, and is “at the same time enlightened and superstitious, proud to be an individualist and in constant fear of not being like all the others, jealous of his independence and inclined to submit blindly to power and authority”. The emerging libertarian-authoritarian personality shares some elements with classical authoritarianism, but does not submit to conventional values, such as discipline, orderliness and diligence. [SG: This is amazing stuff: So, this new “dark” libertarian authoritarian has some features of authoritarianism that are not unique to authoritarianism but does not have the other elements that are unique to authoritarianism. Must be an authoritarian! Utter brilliance] The new authoritarian personality is the paradoxical result of advanced individualism, growing demands for political participation, and access to higher education. [SG: That very much sounds like the exact opposite of authoritarian; but who am I to judge?]

The tendency to reject rules or new laws is increasingly prominent in Western societies. It is a consequence of what researchers call the hyper-empowerment of individuals. Liberal modernity has given rise to numerous institutions – ministries, ombudsmen, labour rights and so on – that improve people’s way of life. More people are being socialised in a post-authoritarian, liberal environment. They were raised in a permissive environment in which authoritarian values such as discipline and unquestioning obedience to power played a lesser role at school, university and at work.

But thanks to their better education, modern libertarians are increasingly sceptical of institutions because they believe they know better than the experts. [SG: Probably better than some second tier sociologists one might say] On the one hand, information access has become democratised; on the other hand, the result of scientific advancements and disciplinary specialisation is that individuals have a poorer understanding of the world that surrounds them.

And yet, people nevertheless want to be equally recognised subjects, albeit not so much with respect to their knowledge, but rather with respect to their opinions. Here is the basis of libertarian authoritarians’ post-truth politics: the inability to know the changing world around them and a yearning for political participation. The authoritarian personality wants all opinions (especially their own) to be taken seriously. [SG: As we all know, that’s ALMOST Arendt’s definition of authoritarianism…NOT!] In late-modern conflicts over freedom, such as the wearing of masks, vaccinations and climate measures, libertarian authoritarians validate their views with proto-scientific evidence, rumours, conspiracy theories and fake news.

Neoliberalism [SG: Of course, the neoliberal Poltergeist needs to be invoked again!], which since the 1980s has portrayed political and social institutions as harmful to markets and individuals, is also an underlying factor behind the rise of this libertarian authoritarianism. Although individuals are as free now as never before, social restraints have not disappeared. Setting oneself apart from the crowd, achieving self-realisation and self-improvement – these requirements are often imposed on us. For example, in many professions, having your own social media profile is no longer optional if you want to stand out. [SG: That is the totalitarian tyranny of modernity y’all. That pressure to post on insta!] It is a necessary part of competing in the labour market. All this takes place in an anxious world in which social and cultural norms constantly change, and late-modern individuals take offence if they can’t fulfil their aspirations for self-development. With their orientation towards self-realisation and authenticity, they seek immanence: that is, they don’t want to change the world, they want to improve themselves – and desire stability in alternative forms of transcendence precisely for this reason. [SG: Pay attention because this is innocent bla bla is a core part of their argument: capitalist material pressures => self-care of the individual => narcissicm and self-glory => esotericism + liberalism => putting oneself as absolute authority => authoritarianism. Of course, non of this is grounded in empirical work but just asserted reddit-style!]

[…]

The anti-lockdown querdenken movement in Germany is an expression of the new libertarian-authoritarian personality. A coalition of anthroposophists, former supporters of the Greens, activists from the old ecology movement demonstrated together with supporters of the hard-right Alternative for Germany party, sovereign citizens and conspiracy theorists. They share a distinctive aggression, superstition, destructiveness and cynicism about vulnerable groups. But they are neither conventional nor submissive to authorities. On the contrary, they often reject all and any social authorities, above all the state and “mainstream” experts. The only authority they recognise is themselves. Freedom is an unconditional value, and they refuse to reconcile it with – let alone restrict it for the benefit of – the freedom of others. They conceive of this freedom as their sole right, which only they dispose of – a kind of reified freedom. They own their freedom like a commodity. In this sense, they are libertarians because they consider their own individual freedom to be absolute. [SG: This paragraph is the essence of their thinking: Freedom does not belong to the individual but is granted to them one a case-by-case basis. Anyone denying this is basically a totalitarian.]

Yet this is simultaneously the proof of their authoritarian inclination. They devalue those who represent or adhere to a concept of freedom that differs from their own. [SG: Bruv, that’s what your whole book is about!] It is this form of aggressive discouragement that makes them libertarian authoritarians.

Criticising state measures that restrict freedom is legitimate and sometimes even desirable. But what emerges from our research in Germany (though the same tendencies can be observed across Europe) is that the form of criticism is permeated by conspiracy theories that traverse right-wing thinking. The conspiracy theories – such as “the great reset”, or that Bill Gates is trying to forcibly vaccinate the world – were also the basis for fantasies of punishment and violence against experts, politicians and opponents. [SG: A casual ad hominem argument. Everyone we don’t like is a conspiracy theorist. Classic!]

Despite their intense critique of liberal democracy, libertarian authoritarians consider themselves democrats. At the same time, they are usually not the fascistic personalities that Horkheimer’s colleague Theodor Adorno considered high-scorers on his F-scale personality test. Today’s libertarian authoritarians have been democratically socialised and profess participatory values. That said, they often have few reservations over standing alongside fascists. They are so disappointed with democracy that they become vulnerable to the authoritarian drift, not only taking a temporary right-wing turn but maintaining such a stance in the long run.

Libertarian authoritarians’ anger is directed against the modern state. [SG: Or in my case against the publisher of this book] It is still a class state. Some social groups, among them men of an advanced age, are losing their uncontested position of power, which they perceive as a loss of freedom. Society’s democratisation, inclusion and equality efforts restrict those subjective freedoms they previously enjoyed in their class and status hierarchies.

Many libertarian authoritarians also consider themselves victims of supposed progressive usurpers (“left-liberal cosmopolitans”), who have seized power over the state, the universities and the media. [SG: I mean tbf, this book is a great case study for that] To them, this entails a new divide: the antagonism between the illiberal rule of the left-liberal elites and the democratic majority, between a higher-educated centre and a hard-working periphery.

[…]

The expansion of democratic inclusion and equality, however, comes at a price, which is causing today’s battles over freedom. Social rights were dismantled along with the move towards democratic inclusion. For workers, the unemployed and the poor, this signified a reduction of their individual liberties. For the established elites, the inclusion of previously excluded groups amounted to a loss of power. In this new power struggle, left-liberals often act exactly like those who have now partially lost their privileges: just like elites. By pursuing a “progressive neoliberalism”, while ignoring material social issues, left-liberalism not only allowed libertarian authoritarians to present themselves as the representatives of “ordinary people” – right-wing populists, too, are eagerly seizing on this opportunity.

The rise of libertarian authoritarianism is also a consequence of the weakness of the left and social movements. [SG: Now, they talk to their target audience] It has often lost its anti-establishment appeal. Many people no longer see the left as sufficiently critical of the state and the media. It is no longer seen as a legitimate representative of a collective criticism of power and a productive counter-knowledge. Social movements such as feminism and the anti-nuclear movement have repeatedly rationalised criticism of power; libertarian authoritarians selectively align themselves with the conspiracy-theory knowledge that only serves to maintain their general suspicion of the (now: left-liberal) elites.

Late-modern societies have entered an era of polycrisis, when all efforts by the political elites to contain the various crises lead to a permanent state of emergency – in which only fictions of normality are maintained. However, because liberalism prevents any real transformation of capitalism or any enlightened thinking about alternatives, it is becoming increasingly paternalistic, and intervening more deeply in individuals’ lives, such as in the fight against climate change. [SG: That sounds like a proper scientific thesis appropriate for an academic book] The austerity policies of the last 25 years also play a part. Citizens were repeatedly told that there was no money, but in crisis situations (such as the financial crisis) there was always enough money. This has produced a deep alienation among citizens, fuelling the rise of libertarian authoritarianism and new forms of ungovernability.

Cohort Change in Political Gender Gaps in Europe and Canada: The Role of Modernization

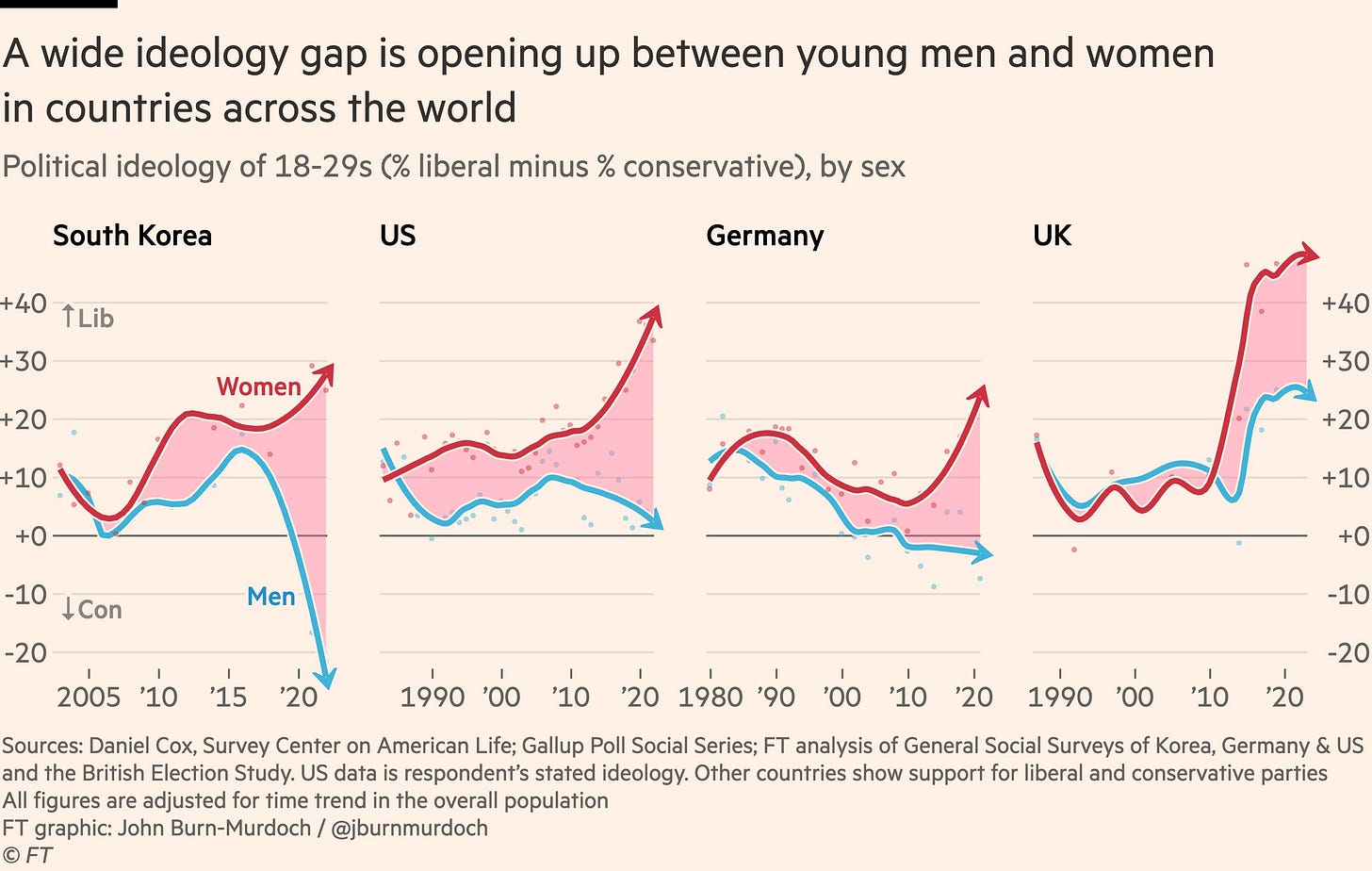

Okay, we have all seen this chart by now:

There is a lot to unpack here—and I will link to some interesting stuff in the upcoming weeks. However, what immediately comes to mind and what seems to be most relevant is the rather robust finding that women usually tend to be more [economically] left-wing than men, but also more religious (both vs. today and vs. men). In essence, religion was a moderating force against those left-wing views. With religion in decline, those views naturally became more prevalent. This ain’t news to the readers of this newsletter; but worth emphasizing in case you think that this sudden gap between men and women is caused by some sort of incel online culture lol. It’s all about the Lord, baby!

Abstract

This article finds firmer evidence than has previously been presented that men are more left-wing than women in older birth cohorts, while women are more left-wing than men in younger cohorts. Analysis of the European Values Study/World Values Survey provides the first systematic test of how processes of modernization and social change have led to this phenomenon. In older cohorts, women are more right-wing primarily because of their greater religiosity and the high salience of religiosity for left-right self-placement and vote choice in older cohorts. In younger, more secular, cohorts, women’s greater support for economic equality and state intervention and, to a lesser extent, for liberal values makes them more left-wing than men. Because the gender gap varies in this way between cohorts, research focusing on the aggregate-level gap between all men and all women underestimates gender differences in left-right self-placement and vote choice.

German railway seeks IT admin to manage MS-DOS and Windows 3.11 systems

At this point, it’s just too easy to dunk on Jermany & Deutsche Bahn. But c’mon:

A job for your grandpa: A German-based railway recently posted a job application for an IT administrator with a peculiar skill set. X user konkretor recently discovered a job listing seeking an IT professional with knowledge of legacy operating systems including Windows 3.11 and MS-DOS. The listing has since been removed but according to the user, the job related to railway display boards widely used in Germany.

Tom's Hardware learned that candidates would oversee machines running 166 MHz processors with 8 MB of RAM, which are used to display important technical train data to operators in real-time.

[…]

Legacy hardware and operating systems are battle tested, having been extensively probed and patched during their heyday. The same can be said for software written for these platforms – they have been refined to the point that they can execute their intended tasks without incident. If it ain't broke, don't fix it.

One could also argue that dated platforms are less likely to be targeted by modern cybercriminals. [SG: The most pathetic argument I’ve heard in a long while!] Learning the ins and outs of a legacy system does not make sense when there are so few targets still using them. A hacker would be far better off to master something newer that millions of systems still use.

Legacy systems are far more common than most realize, and are still used to run mission critical systems. Some airplane manufacturers still use floppy disks to apply service updates to older aircraft. Chuck E. Cheese used foppies to run its animatronics for years, and it wasn't until 2019 that the US military stopped using IBM Series-1 computers from the 1970s in nuclear weapons systems.

It is unclear if the German railway operator found a new admin, or if they simply took down the listing out of embarrassment. If your grandfather is looking for a new job, perhaps drop him a line so he can mail in his application.

What Good Friends Look Like

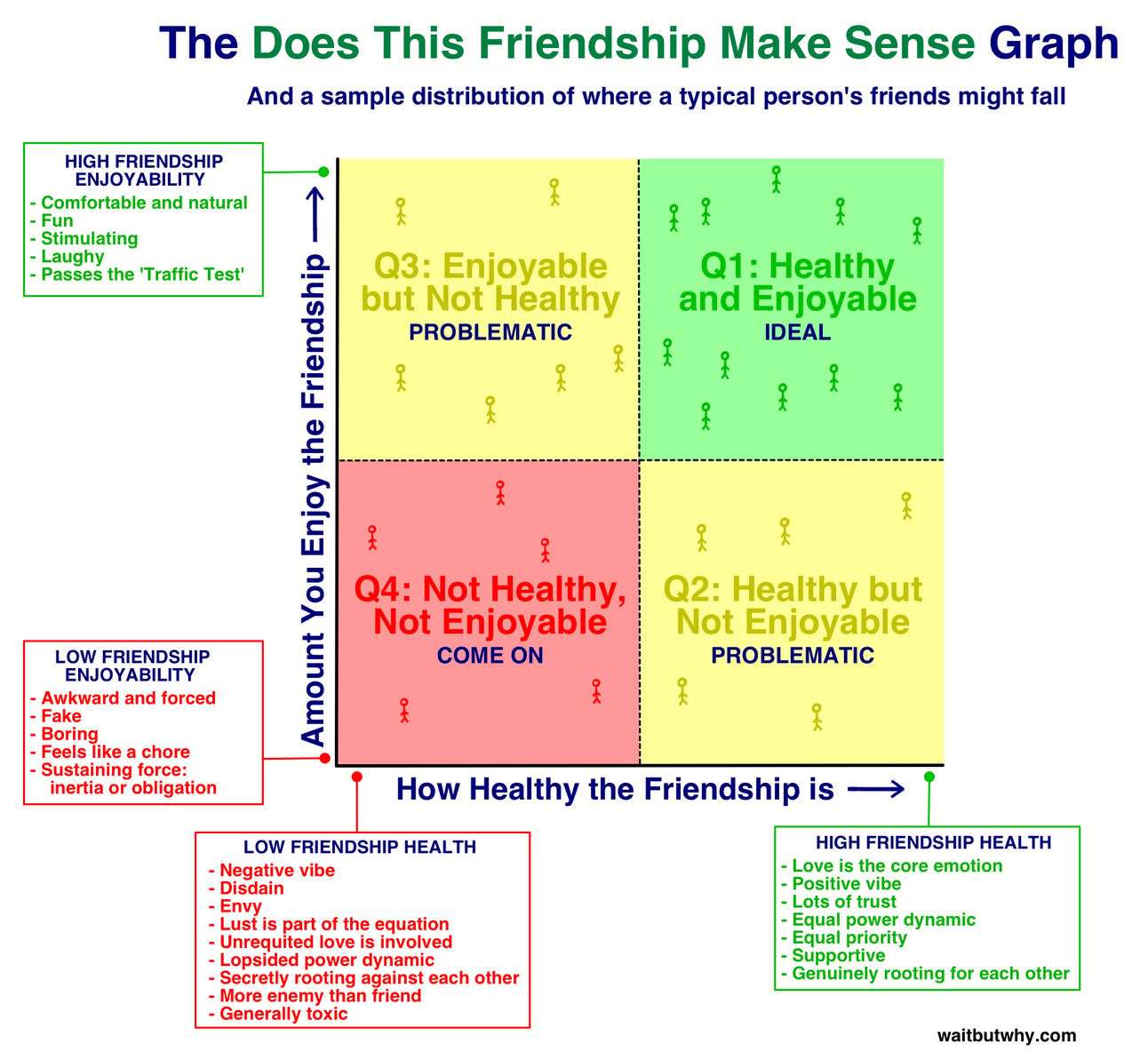

My INTJ x BCG brain just loves the idea of putting friendships into a matrix. And so should you. This is a piece of brilliance and probably the most useful thing you will read this week!

…and yes, I know that I’m in Q2 for most of you 🥹

(s/o to the ones that experienced my Q3 qualities tho 😏)

Tim Urban provides a look at friendship from a qualitative standpoint. Use this powerful matrix to evaluate your friendships and to discover which relationships are worth maintaining.

Friendship health is on the x-axis, and enjoyability is measured on the y-axis. Highly enjoyable friendships feel easy and natural. With these friends, conversation flows without awkward pauses. They make you feel stimulated and excited.

Highly enjoyable friendships pass Tim Urban’s traffic test: You and the friend are in the car together driving home. If you’re rooting for traffic because the conversation is so good, they pass.

If you encounter traffic and feel a sense of dread, they don’t pass.

These friendships:

Make everything—even airport delays or long restaurant wait times—fun

Stimulate your mind

Make you excited to see the other person

Involve common interests and shared experiences

[…]

Low-enjoyability friendships are those that feel like a chore. If you’re considering canceling on the other person, despite not having other things to do, they’re likely a low-enjoyability friend.

In low enjoyability friendships:

Conversation feels awkward or boring

You don’t look forward to seeing the other person

You leave feeling exhausted

Are guided by obligation or necessity

Highly healthy friendships feel positive and supportive. You would do anything for them, and they would do the same for you. These friendships take years to form, but they’re worth every moment. They’re built on love and respect.

You’re genuinely happy when these friends succeed. There’s no resentment or jealousy.

Highly healthy friendships are:

Rooted in positivity and love for one another

Trusting

Absent of a lopsided power dynamic

Supporting

Unhealthy friendships, or those with a low health rating, are generally toxic. These friendships are rooted in obligation, blame, and mutual disdain. For example, if you’re on a coffee date with these friends, you can’t wait to leave. You’re not just bored, you’re annoyed.

Unhealthy friendships are often lopsided: One of you feels strongly for the other, and wants to maintain a connection, while the other does not.

An unhealthy friend feels jealous when the other receives a promotion or accomplishes a goal. There is envy present.

These friends are:

Full of residual blame, disdain, and jealousy

More enemies than friends

Rooting for the other’s failure

Generally negative

Let’s think more specifically.

Q1 friendships are healthy and enjoyable. Friends in this area are Tier 1 friends, and you’d do anything for them. Not only that, but you’re genuinely happy for their accomplishments. These friends will give speeches at your wedding, and you’ve formed an eternal relationship. If the two of you encounter a disagreement, you’re both confident that your friendship will survive.

[…]

Q2 friends are healthy, but not enjoyable. They might be loose friends, acquaintances, or coworkers. These relationships don’t involve the blame and resentment present in Q4 friendships, but you don’t look forward to seeing them regularly.

For example, let’s say your co-worker helps you manage a project deadline. The two of you have a healthy relationship, but you wouldn’t ask them to speak on your wedding day.

[…]

Q3 relationships aren’t healthy, but they’re fun. Romantic relationships and those with your childhood friends often fall into this category. These involve an unhealthy power dynamic, resentment, and blame, or are unrequited.

If you’re excited to be around the other person but know that you’ll need to be guarded in some way, you’re likely looking at a Q3 friend.

These people drain your energy, make you feel self-conscious, and generally, aren’t there for you if need be.

[…]

Q4 friends aren’t friends at all. These people would be enemies, or those you generally avoid. These friendships could be those that have fizzled out or those you can’t stand to maintain. Most of us have a few Q4 friends, and it’s time to get rid of them. Avoid Q4 friends at all costs.

[…]

Good friends are easily available, but great (Q1) friends are difficult to come by.

Friendships are an important component of socialization. Keeping and maintaining positive friendships isn’t easy, but understanding others’ role in your life is crucial.

Peace,

SG