On a Personal Note

Unfortunately, I missed last week’s newsletter—due to Deutsche Bahn (no surprise there). That is the reason why I couldn’t link to my podcast with the excellent Philipp Mattheis. We talked about why libertarians have a bad rep, populism, Milei, Bitcoin, and much more. Check out the whole interview (unfortunately, only in German!), subscribe to Philipp’s newsletter, and buy his book on the Chinese Belt & Road Initiative (“Die Dreckige Seidenstraße” // “Dirty Silk Road”). We hosted Philipp at one of our IAF seminars in Gummersbach and it was a blast. Hopefully, more to come in the future.

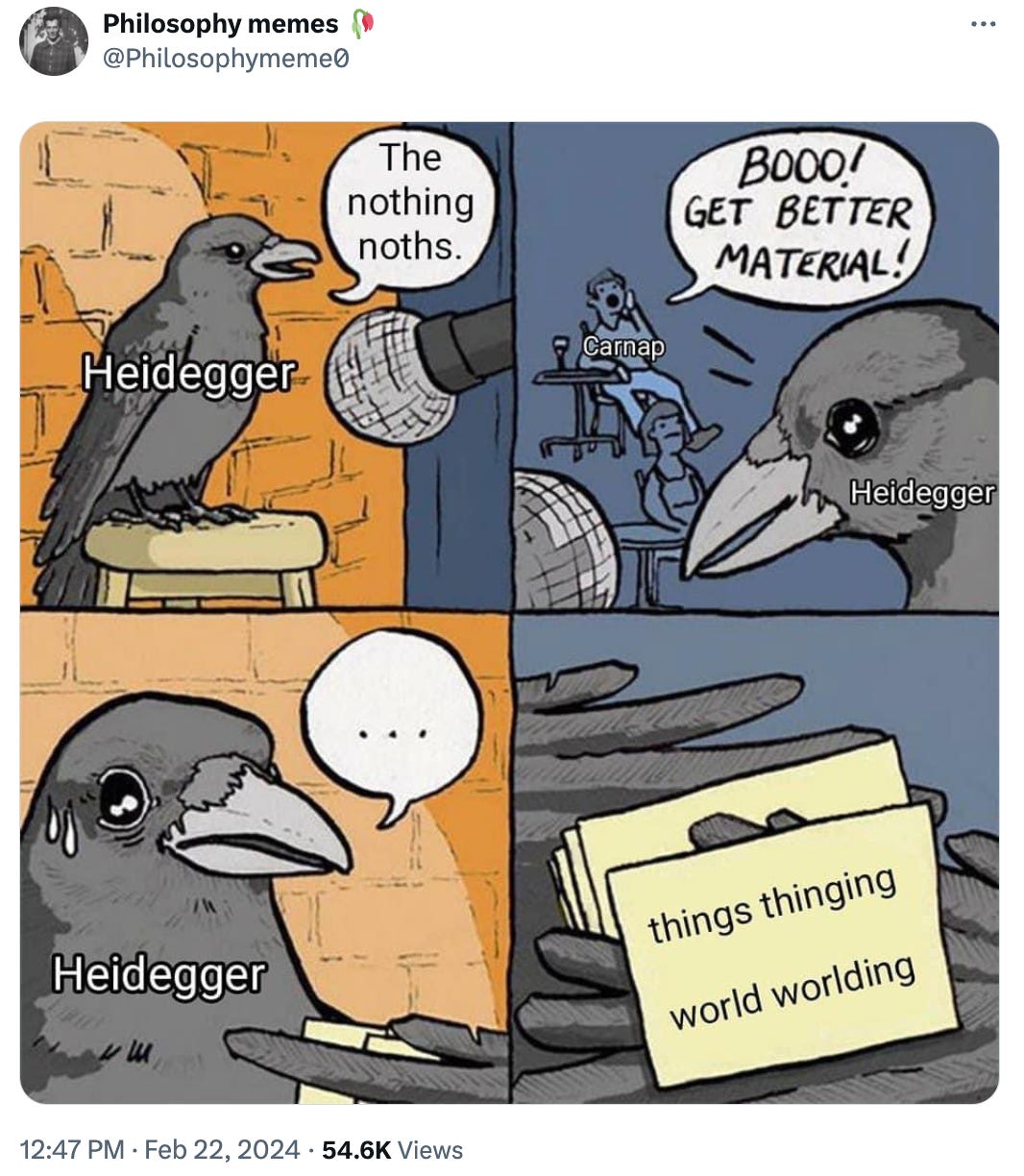

Moreover, I gave a little lecture on Heidegger. Preparing for that, I was sharing my thoughts with my mum during lunch: “So, Heidegger thinks that modern metaphysics has wrongfully abandoned the question of Being. For example, when we say that “the sky is blue”, philosophers are only interested in the concept of the ‘sky’ or the properties of ‘blue’; but they don’t ask about the ‘is’…the Being of the sky.” At this point, she turned to me and literally asked me whether I had lost my mind. Well :(

What If Money Expired?

This is a paradoxical read: On the one hand, I really enjoyed the (often overlooked) conceptual debate about the nature of money; on the other hand, there are so many apparent technical flaws in the representation of the argument that it is tricky to recommend. However, the last paragraph should maybe set the context and tonality of why I would nevertheless say that it is worth having a look at the article:

Is his idea of an expiring currency any more absurd than the status quo we inherited? Perhaps his greatest contribution is to remind us that the rules of money can be reinvented, as indeed they always have. Money is a construct of our collective imagination, subject to our complacency, yes, but also to our inquiry, values and highest ambitions. Gesell argued for an engaged, probing curiosity of our economic institutions so that we may reimagine them to better serve the societies we want to create. “The economic order under which men thrive,” he wrote, “is the most natural economic order.” To that end, ours may still be a work in progress.

This is exactly the spirit that initially attracted me to the debates around Bitcoin. Because in the early days, the Bitcoin forums were not about speculation or financial hedging; but about the imagination to design an economic order under which men could thrive. Yet, unlike Silvio Gesell (the main inspiration for this piece), Bitcoiners and Austrians (including myself) advocate for a society of low time preference versus the hyper-consumerist high time preference society of instant gratification that we live in…and that a Gesellian monetary system would basically put on steroids. (For more on this, check out Chapter 5 of “The Bitcoin Standard”)

A couple of things are worth mentioning here: First, this “aspiration” of a depreciating currency is actually (!) our day-to-day reality. While the author does not spend a single line talking about inflation, we can observe in our contemporary fiat world that you don’t need a Gesellian system of accelerated money to depreciate a currency. Money printing and QE are doing a job at achieving the same goal. Second, Gesell might be a fringe economist; but (as the article nicely highlights) his ideas had a profound impact on thinkers, such as John Maynard Keynes. Third, there is a deeply anti-Semitic sentiment in Gesell’s views on money lending. And last, Gesell himself was a German-Argentinian money theorist…make out of that whatever you want lol. Needless to say that these ideas lead to deeply authoritarian tendencies—as you would need to prohibit all alternative stores of values in order to get the desired consequences. In any case, read the whole piece, even though it often has the vibe of economics that only a journalist would consider groundbreaking:

More than a century ago, a wild-eyed, vegetarian, free love-promoting German entrepreneur and self-taught economist named Silvio Gesell proposed a radical reformation of the monetary system as we know it. He wanted to make money that decays over time. Our present money, he explained, is an insufficient means of exchange. A man with a pocketful of money does not possess equivalent wealth as a man with a sack of produce, even if the market agrees the produce is worth the money.

“Only money that goes out of date like a newspaper, rots like potatoes, rusts like iron, evaporates like ether,” Gesell wrote in his seminal work, “The Natural Economic Order,” published in 1915, “is capable of standing the test as an instrument for the exchange of potatoes, newspapers, iron and ether.”

[…]

He argued that the properties of money — its durability and hoardability — impede its circulation: “When confidence exists, there is money in the market; when confidence is wanting, money withdraws.”

Those who live by their labor suffer from this imbalance. If I go to the market to sell a bushel of cucumbers when the cost of food is falling, a shopper may not buy them, preferring to buy them next week at a lower price. My cucumbers will not last the week, so I am forced to drop my price. A deflationary spiral may ensue.

The French economist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon put it this way: “Money, you imagine, is the key that opens the gates of the market. That is not true — money is the bolt that bars them.”

The faults of money go further, Gesell wrote. When small businesses take out loans from banks, they must pay the banks interest on those loans, which means they must raise prices or cut wages. Thus, interest is a private gain at a public cost. In practice, those with money grow richer and those without grow poorer. Our economy is full of examples of this, where those with money make more ($100,000 minimum investments in high-yield hedge funds, for example) and those without pay higher costs (like high-interest predatory lending).

“The merchant, the workman, the stockbroker have the same aim, namely to exploit the state of the market, that is, the public at large,” Gesell wrote. “Perhaps the sole difference between usury and commerce is that the professional usurer directs his exploitation more against specific persons.”

Gesell believed that the most-rewarded impulse in our present economy is to give as little as possible and to receive as much as possible, in every transaction. In doing so, he thought, we grow materially, morally and socially poorer. “The exploitation of our neighbor’s need, mutual plundering conducted with all the wiles of salesmanship, is the foundation of our economic life,” he lamented.

[…]

To correct these economic and social ills, Gesell recommended we change the nature of money so it better reflects the goods for which it is exchanged. “We must make money worse as a commodity if we wish to make it better as a medium of exchange,” he wrote.

To achieve this, he invented a form of expiring money called Freigeld, or Free Money. (Free because it would be freed from hoarding and interest.) The theory worked like this: A $100 bill of Freigeld would have 52 dated boxes on the back, where the holder must affix a 10-cent stamp every week for the bill to still be worth $100. If you kept the bill for an entire year, you would have to affix 52 stamps to the back of it — at a cost of $5.20 — for the bill to still be worth $100. Thus, the bill would depreciate 5.2% annually at the expense of its holder(s). (The value of and rate at which to apply the stamps could be fine-tuned if necessary.)

This system would work the opposite way ours does today, where money held over time increases in value as it gathers interest. In Gesell’s system, the stamps would be an individual cost and the revenue they created would be a public gain, reducing the amount of additional taxes a government would need to collect and enabling it to support those unable to work.

Money could be deposited in a bank, whereby it would retain its value because the bank would be responsible for the stamps. To avoid paying for the stamps, the bank would be incentivized to loan the money, passing on the holding expense to others. In Gesell’s vision, banks would loan so freely that their interest rates would eventually fall to zero, and they would collect only a small risk premium and an administration fee.

With the use of this stamp scrip currency, the full productive power of the economy would be unleashed. Capital would be accessible to everyone. A Currency Office, meanwhile, would maintain price stability by monitoring the amount of money in circulation. If prices go up, the office would destroy money. When prices fall, it would print more.

In this economy, money would circulate with all the velocity of a game of hot potato. There would be no more “unearned income” of money lenders getting rich on interest. Instead, an individual’s economic success would be tied directly to the quality of their work and the strength of their ideas. Gesell imagined this would create a Darwinian natural selection in the economy: “Free competition would favor the efficient and lead to their increased propagation.”

This new “natural economic order” would be accompanied by a reformation of land ownership — Free Land — whereby land was no longer privately owned. Current landowners would be compensated by the government in land bonds over 20 years. Then they would pay rent to the government, which, Gesell imagined, would be used for government expenses and to create annuities for mothers to help women achieve economic independence from men and be free to leave a relationship if they wanted.

Gesell’s ideas salvaged the spirit of private, competitive entrepreneurialism from what he considered the systemic defects of capitalism. Gesell could be described as an anti-Marxian socialist. He was committed to social justice but also agreed with Adam Smith that self-interest was the natural foundation of any economy.

While Marx advocated for the political supremacy of the dispossessed through organization, Gesell argued that we need only remove economic obstacles to realize our true productive capacity. The pie can be grown and more justly shared through systemic changes, he maintained, not redistributed through revolution. “We shall leave to our heirs no perpetually welling source of income,” he wrote, “but is it not provision enough to bequeath economic conditions that will secure them the full proceeds of their labor?”

Although many dismissed Gesell as an anarchistic heretic, his ideas were embraced by major economists of the day. In his book “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,” John Maynard Keynes devoted five pages to Gesell, calling him a “strange and unduly neglected prophet.” He argued the idea behind a stamp scrip was sound. “I believe that the future will learn more from the spirit of Gesell than from that of Marx,” Keynes wrote.

[…]

To [Ezra] Pound [SG: another Gesellian evangilist], money that is organic, subject to birth and decay, that flows freely between people and facilitates generosity, is more likely to bind a society together rather than isolate us. An expiring money would enrich the whole, not the select few. Usury — which we can take to mean unfettered capitalism — was responsible for the death of culture in the post-Reformation age.

Pound eventually moved to Italy and embraced the fascism of Benito Mussolini, advocating for a strong state to enforce these ideas. [SG: LOL] In doing so, he ceded his artistic idealism to autocratic fiat. Pound was strident in his economic convictions but also a realist on human nature. “Set up a perfect and just money system and in three days rascals, the bastards with mercantilist and monopolist mentality, will start thinking up some wheeze to cheat the people,” he wrote.

[…]

Gesell’s idea for depreciating money “runs counter to anything we’ve ever learned about the desirable properties of money,” David Andolfatto, a former senior vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the chair of the economics department at the University of Miami, told me recently. “Why on Earth would you ever want money to have that property?”

But during the economic downturn that followed the Covid pandemic, Andolfatto recognized the potential value of an expiring money in times of crisis. The relief checks that the government sent out to U.S. households didn’t immediately have their desired effect of stimulating the economy because many people saved the money rather than spend it. This is the paradox of thrift, Andolfatto explained. What’s good for the individual is bad for the whole.

“Well, what if we gave them the money with a time fuse?” Andolfatto remembers wondering. “You’re giving them the money and saying look, if you don’t spend it in a period of time, it’s going to evaporate.”

In a paper he wrote for the Fed in 2020, Andolfatto called this concept “hot money credits.” He pointed out that when the economy goes into a funk, there is a “coordination failure” where people stop spending and others stop earning. Withholding money in times of fear creates a self-fulfilling prophecy by further stifling the economy. So, could Gesell’s idea of expiring money be the cure?

“The desirability depends on the diagnosis,” Andolfatto told me. “It’s like a doctor administering a drug to a healthy person and a sick person. You administer the drug, and it has some side effects. If the person is healthy, you’re not going to make them any better. You might make them even worse. If they’re sick, it might make them better.”

The problem, Andolfatto said, is that issuing pandemic checks with an expiration date would hurt those with little savings. People with money in the bank would use their expiring money just like normal money. People with no savings, on the other hand, might find that expiring money forced them to spend and did little to stabilize their financial situations.

[…]

Keynes believed Gesell’s expiring money amounted to “half a theory” — it failed, Keynes argued, to account for people’s preference for liquid assets, of which money is just one example. “Money as a medium of exchange has to also be a store of value,” Willem Buiter, a former global chief economist at Citigroup, told me. In a Gesellian economy, he continued, the affluent would simply store their wealth in another form — gold bars, perhaps, or boats — which could be converted into money when they wanted to transact.

Buiter doesn’t believe Gesellian money can really address serious social inequality, but he did note times when it was advantageous for a central bank to drop interest rates below zero, like when inflation and market interest rates are low and should go lower to maintain full employment and utilization of resources. Positive or negative interest rates could easily be applied to digital money in a cashless economy, for which Buiter and others have advocated. But it’s hard to imagine how a government today could practically implement a Gesellian tax on hard currency. “You’d have to be able to go out and confiscate money if it’s not stamped,” Buiter said. “It would be rather brutal.”

The Death of Alexey Navalny, Putin’s Most Formidable Opponent

It rarely happens that I feel truly devastated. But the news about the death of Alexey Navalny was one of those moments. I met Navalny in 2019 at the Boris Nemtsov Forum in Warsaw—where I was speaking on a panel with Vladimir Kara-Murza. At that time, my core argument was something like this: The Russian opposition (including Navalny) still makes the conceptual mistake of not treating Putin as what he is: a full-fleshed dictator—which IMHO had severe implications for the tactics of resistance (i.e. the anti-corruption narrative won’t fly). Doesn’t look like wrong guidance in hindsight, I must say. But I am not saying this to praise myself; but rather to give context to my encounter with Navalny. Because the Navalny that I met in Warsaw (and with whom I had a brief exchange) was very much like the person that the excellent Masha Gessen portrays in this article: Incredibly charismatic, human, surprisingly naive in the way he underestimated the evil nature of the Kremlin regime, and always open to a good argument. Obviously, my friends from the post-Soviet space would accuse me of taking the Western view of glorifying just another closet Russian imperialist and ethno-nationalist…but one the West likes because he is anti-Putin. Don’t fall for this. This sort of Kremlin-style fabricated BS ain’t true. The legacy of Navaly is what Gessen put here on paper. I am glad she did:

Alexey Navalny spent at least a decade standing up to the Kremlin when it seemed impossible. He was jailed and released. He was poisoned, and survived. He was warned to stay away from Russia and didn’t. He was arrested in front of dozens of cameras, with millions of people watching. In prison, he was defiant and consistently funny. For three years, his jailers put him in solitary confinement, cut off his access to and arrested his lawyers, piled on sentence after sentence, sent him all the way across the world’s largest country to serve out his time in the Arctic, and still, when he appeared on video in court, he laughed at his jailers. Year after year, he faced down the might of one of the world’s cruellest states and the vengeance of one of the world’s cruellest men. His promise was that he would outlive them and lead what he called the Beautiful Russia of the Future. On Friday, they killed him. He was forty-seven years old.

[…]

In Russia, Vladimir Putin was visiting an industrial park in Chelyabinsk, in the Urals. He took questions from staff and students, who were seated a safe distance from the Russian President on what appeared to be the plant floor. Putin seemed to be in an unusually good mood. He bantered and flirted with the audience. He boasted that Western sanctions in response to the war in Ukraine had boosted industrial production inside Russia. He hadn’t seemed so jovial in public in years.

[…]

It’s tempting to see Navalny’s apparent murder, as some American analysts have, as a sign of weakness on the part of Putin. But a dictator’s ability to annihilate what he fears is a measure of his hold on power, as is his ability to choose the time to strike. Putin appears to be feeling optimistic about his own future. As he sees it, Donald Trump is poised to become the next President of the U.S. and to give Putin free rein in Ukraine and beyond. Even before the U.S. Presidential election, American aid to Ukraine is stalled, and Ukraine’s Army is starved for troops and nearing a supply crisis. Last week, Putin got to lecture millions of Americans by granting an interview to Tucker Carlson. At the end of the interview, Carlson asked Putin if he would release Evan Gershkovich, a Wall Street Journal reporter held on espionage charges in Russia. Putin proposed that Gershkovich could be traded for “a person, who out of patriotic sentiments liquidated a bandit in one of the European capitals.” It was a reference to Vadim Krasikov, probably the only Russian assassin who has been caught and convicted in the West; he is held in Germany. A week after the interview aired, Russia has shown the world what can happen to a person in a Russian prison. It’s also significant that Navalny was killed on the first day of the Munich conference. In 2007, Putin chose the conference as his stage for declaring what would become his war against the West. Now, with this war in full swing, Putin has been excluded from the conference, but the actions of his regime—the murders committed by his regime—dominate the proceedings.

Russian prison authorities have said that Navalny felt ill after returning from his daily walk, lost consciousness, and could not be revived. They have ascribed his death to a pulmonary embolism. Anna Karetnikova, a prisoners’-rights activist and a former member of the civilian-oversight body of Russia’s prison system, has said that prison authorities routinely use embolism as a catchall term. Sergey Nemalevich, a journalist with the Russian Service of Radio Liberty, noticed that the ostensible timing of the death didn’t seem to jibe with Navalny’s recent description of his schedule in solitary confinement: he had said that his daily walk took place at six-thirty in the morning, but prison authorities claimed that, on the day of his death, he returned to his cell in the afternoon. Nemalevich suggested that Navalny was dead long before an ambulance—which authorities said took a mere seven minutes to travel twenty-two miles to the prison—was called to declare him dead.

Navalny, who was educated as a lawyer, became active in politics in the early two-thousands and emerged as a public figure around 2010. His early politics were ethno-nationalist, at times overtly xenophobic, and libertarian. He advocated for gun rights and a crackdown on migrants. But he found his agenda and his political voice in documenting corruption. He built a movement based on the premise that citizens, even in Russia, could and should exercise control over the way that government money is spent. In the ensuing years, he evolved from an ethno-nationalist to a civic nationalist, from a libertarian to a social democrat. He learned new languages, read incessantly, and incorporated new ideas into his program. He focussed, increasingly, not only on political power but on social welfare. During the past three years, he used the pulpit provided by an endless series of court hearings to air his political views. In a courtroom speech on February 20, 2021, he outlined a vision for a country with a better health-care system and a more equitable distribution of wealth. He proposed changing the slogan of his political movement from “Russia will be free” to “Russia will be happy.” He continued to assert this hopeful agenda, even as he grew more and more gaunt and even as he was forced to appear in court on a video screen, separated from his audience by glass, a grate, and thousands of miles.

Navalny’s public voice was full of irony without being cynical. He saw the targets of his investigations as ridiculous men with large yachts, small egos, and staggeringly bad taste. He took their abuses seriously by cutting them down to size. This was half of his charisma. The other half was his love story. More than anything else in the world, it seemed, he wanted to impress Yulia. Confined to a cube in a courtroom, he put his hands in the shape of a heart, gesturing at her. He sent love notes from prison, which were posted to social-media for him.

[…]

A year after the Kremlin’s attempt to put Navalny away failed, Putin took a hostage: Alexey’s brother Oleg was jailed on trumped-up charges. It was an old reliable tactic. The henchmen assumed that, with Oleg behind bars, Alexey would cease his political activities to keep his brother safe. But the brothers made a pact to keep going. Alexey built a sprawling organization that expanded far beyond documenting corruption. He ran for mayor of Moscow. He built a network of political offices that could have enabled a Presidential race if such a thing as elections actually existed. He grew frustrated that journalists weren’t following his leads or undertaking investigations of their own, and so he founded his own media: YouTube shows and Telegram channels that publicized the results of his group’s investigations. Navalny’s work spawned an entire generation of independent Russian investigative media, many of which continue working in exile, documenting not only criminal assets but also war crimes and the activities of Russia’s assassins at home and abroad.

The state harassed Navalny, placed him under house arrest, pushed the organization out of its offices, jailed some of its activists and forced the rest into exile, declared them “extremists,” and started going after people who had donated even a small amount of money to the group. Then, in August, 2020, the F.S.B. poisoned Navalny with Novichok, a chemical weapon. He was meant to die on a plane. But the pilot made an emergency landing, doctors administered essential first aid, and Yulia took over the superhero role, pressuring the authorities to let her take Alexey to Germany for treatment.

After weeks in a coma, Navalny emerged and teamed up with another investigator, Christo Grozev, a Bulgarian journalist then working with Bellingcat. Grozev got the receipts: the flight manifests that showed that Navalny had been trailed by a group of F.S.B. agents, some of whom also happened to be chemists. Navalny supplied the performative flair. He called his would-be murderers on the phone and managed to get a guileless confession out of one, complete with the detail of where the poison had been placed: in the crotch area of Navalny’s boxer shorts. The scene would later be incorporated into the film “Navalny,” which won an Oscar for Best Documentary, but, before that, Navalny put it in his own made-for-YouTube movie, titled “I Called My Killer. He Confessed.” It was released on December 21, 2020.

A month later, Navalny flew back to Moscow. His friends had tried to talk him out of it. He wouldn’t hear of staying in exile and becoming politically irrelevant. He imagined himself as Russia’s Nelson Mandela: he would outlive Putin’s reign and become President. Perhaps he believed that the men he was fighting were capable of embarrassment and wouldn’t dare to kill him after he’d proved that they had tried to. He and I had argued, over the years, about the fundamental nature of Putin and his regime: he said that they were “crooks and thieves”; I said that they were murderers and terrorists. After he came out of his coma, I asked him if he had finally been convinced that they were murderers. No, he said. They kill to protect their wealth. Fundamentally, they are just greedy.

He thought too highly of them. They are, in fact, murderers.

All over Russia on Friday, people were laying flowers in memory of Navalny. In the few cities where memorials exist to past victims of Russian totalitarianism, these monuments became the destinations. Police were breaking up gatherings, throwing out flowers, and detaining journalists.

The Politics of Mate Choice

This adds to the hypothesis that values are the main driver of successful relationships—and why all my experiments with socialists ultimately fell flat. Obviously, this has many implications in increasingly polarized societies:

Correlations between spouses:

Extraversion: r= .005

Neuroticism: .082

Height: .227

Weight: .154

Education: .5

Political party: .6

Abstract

Recent research has found a surprising degree of homogeneity in the personal political communication network of individuals but this work has focused largely on the tendency to sort into likeminded social, workplace, and residential political contexts. We extend this line of research into one of the most fundamental and consequential of political interactions—that between sexual mates. Using data on thousands of spouse pairs in the United States, we investigate the degree of concordance among mates on a variety of traits. Our findings show that physical and personality traits display only weakly positive and frequently insignificant correlations across spouses. Conversely, political attitudes display interspousal correlations that are among the strongest of all social and biometric traits. Further, it appears the political similarity of spouses derives in part from initial mate choice rather than persuasion and accommodation over the life of the relationship.

The Friendship Problem

Some weeks ago, I promised that I would write more on the nature of friendship—and then forgot about it. This seems like a perfect analogy for the way we treat friendship in contemporary societies: As something that we forget about amidst the endless storm of world events that deprive our focus of what ultimately matters. So, here we go: I am resuming the conversation as we do it with those semi-dead WhatsApp chats.

Now, this article does what the best sort of cultural critique does: starting from a mundane yet true observation—namely that most of our friendships feel like admin. As somebody who is very (!) guilty of this, I could relate way too much to this:

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about what’s going on with my friendships, or to be more specific, my lack thereof. I’m not quite sure when it happened, but I’ve felt the presence of friendship dwindle in my life in the past couple years.

[…]

[I]t seems normal now that plans are made far in advance — scheduled around myriad travel and wedding weekends and kids and work commitments — and then canceled right before. Someone doesn’t follow up, or cancels and then never proposes an alternative plan. Similarly, promising new adult friendships never seem to blossom into the kind of quotidian check-ins and week-to-week ephemera that the friendship of our younger years is based on. Life-long friends make new life choices, drift apart. The friendship fizzles into WhatsApp volleys back and forth, and then someone doesn’t answer the last message, and then it’s a year before you ever talk again.

Friendship starts to feel strikingly similar to admin. Sound familiar?

Much has been written about the struggle to make friends once you enter your 30s and beyond, so in some sense this is all nothing new. But for a long time, I’ve detected a level of avoidance, a pathological burnout among many people I know, and in myself — something that suggests a deeper cause is at the core of this. I know I can’t be the only one craving a kind of social connection and nourishment that the seven messaging apps on my phone don’t provide.

[…]

I want to be clear here that the point I am making is not Millennials Killed Friendship. Nor am I calling out any particular friends of mine; I am as guilty of this as anyone. But I am trying to figure out the matrix of factors that leads to a situation where in theory, I have friends — actually loads of them if you look at my phone — but in practice — in the kind of relational, low-stakes, intimate way I crave — there’s a lot to be desired.

I’ve been thinking about this for months, and then one day I heard the eminently quotable Esther Perel address it on a podcast (interview starts at about the 50:00 mark). I’m going to quote her heavily, because I hope the words will stay with you as they did me.

“Modern loneliness masks itself as hyper connectivity. And so people have easily 1000 virtual friends, but no one they can ask to feed their cat. That loneliness, which is really a depletion of the social capital, is extremely powerful. […]

One question I keep asking that I had no idea was going to be so pertinent: When you grew up, did you play freely on the street? … And the majority of the people learned to play freely on the street. They learned social negotiation. They learned unscripted, un-choreographed, unmonitored interaction with people. They fought, they made rules, they made peace, they made friends, they broke up, they made friends again. They developed social muscles. And the majority of these very same people’s children do not play freely on the street. And I think that an adult needs to play freely on the street as well.

For us as adults, that means talking to people in the queue with you, talking to people on the subway, talking to people when you create any kind of group. Book club, movie club, sports club. You stay in the practice of experimentation, doubt, of the paradox of people: You need people very much but the very people that you need are the ones that can reject you.

We do not have the practice at the moment. Everything about predictive technologies is basically giving us a form of assisted living. You get it all served in uncomplicated, lack of friction, no obstacles and you no longer know how to deal with people. Because people are complex systems. Relationships, friendships are complex systems. They often demand that they hold two sides of an equation. And not that you solve little problems with technical solutions. And that is intrinsic to modern loneliness.”

Friendships are, by their very nature, made of friction. To know what is going on in someone’s day-to-day life, to make plans with them, and then reschedule those plans when someone inevitably gets sick, and then bring over Calpol or soup or an extra laptop charger. To water their plants while they’re away, to ask them to take your kids when you’re feeling sad, or for help getting rid of mice in your house. To show up for the walk you planned even when you’re a vulnerable anxious mess — this is all friction.

And friction is not just interrupting your day or life to help out a friend, but also admitting you need the kind of help you cannot pay for or order yourself. To pierce through your veil of seamless productivity and having-it-together to say: I need something from you, can you help me?

Myself and people my age have been trained under the illusion that we can effectively eliminate any and all friction from our lives. We can work from home, Amazon prime everything we need, swipe through a limitless array of mediocre dates, text our therapist, and have a person go to the grocery store for us when we don’t feel like it, all while consuming an endless stream of entertainment options that we’ll scarcely remember the name of two weeks in the future.

All of this creates a kind of “social atrophy” as Perel calls it. We are so burned out by our data-heavy, screen-based, supposedly friction-free lives that we no longer have the time or energy to engage in the kind of small, unfabulous, mundane, place-based friendships or acquaintance-ships that have nourished and sustained humans for literal centuries.

Add in the pandemic, which I think has accelerated this, and we’ve lost entire categories of social interaction that used to foster friendships, especially low key ones. Our lives are bereft of ways to see people in the low-effort, regular, and repeating ways our brains were designed to connect through.

[…]

And let’s not forget, as we all bumble along, burned out, isolated, and drowning in the demands of whatever life or career stage we’re at, we’re also expected to constantly consume and metabolize horrific world events in the background. This over-reliance on tech for every aspect of our lives “opens us up to new vectors of anxiety,” as this great post by Brett Scott put it, with “[our nervous systems] now plugged into a neurotic and hypersensitive globe-spanning information system that’s constantly pushing unnecessary things into your consciousness.”

So is it really any wonder that we might not be inclined to text our friend back about that plan four Thursdays from now, in between consuming images of genocide presented without any context or verifiable information, while trying to order dinner on our phone, and answer a Slack message after hours?

I feel like I say this all the time, but it bears repeating: Our brains were simply not designed to operate this way. The oft-cited Dunbar’s number — that our brains have a cognitive upper limit of about 150 relationships we can actively maintain — can easily be maxed out by a morning Instagram scroll and answering your email and WhatsApps.

And there, I think, lies the crux of the friendship problem: We are so burned out by the process of staying afloat in a globalized, connected world that we simply don’t have the energy for the kinds of in-person, easy interactions that might actually give us some energy and lifeforce back.

[…]

It’s liberation from the idea that we can self-optimize ourselves to the point of not needing anyone else. That if we work hard enough to survive in a competitive economy, we’ll be able to buy, order, or summon anything we might need within 24 hours, and that is somehow progress. That instead of asking for help and support from the people and friends we know — they’re too burned out, don’t want to bother them, they live too far away — we should invest heavily in self care to inoculate ourselves from needing to ask anything of anyone.

These are all ideas that capitalism loves — more people living in their own atomized fiefdoms means selling more stuff and services and meal kits to keep up with the relentless pace of life — but are fundamentally antithetical to the ways that humans are designed to flourish.

It’s certainly no coincidence that my childhood was defined by “playing on the street,” as Perel called it, which is perhaps why I miss the adult version so much. I think we have to choose to go into situations where we don’t know how they might pan out. Be willing to talk or engage with people who don’t share the carefully calibrated views that we broadcast online. In addition to making the effort with friends — new, old, promising acquaintances — and asking for the kind of help and support we need, as well as providing it in return. These are all muscles we need to rebuild.

But in order for this all not to feel like yet more admin, it’s crucial to remember we are not machines. We need to make changes to regain the capacity to show up for these kinds of interactions and relationships. I know if I want to be available for more of the kind of recurring, place-based relationships where I can give and receive support, that means I have to be less available for other things. Mostly, the shiny things inside my phone that loudly insist someone else, somewhere else, is doing or saying or something I should know about.

Kinda nice

kind > nice

(Actually, to be a nice person is actually pretty bad. Don’t be nice!)

A kind person will help you understand reality as it is, prompt you to reflect, and nudge you to fine-tune your position till you get to a place where your resolution is helpful for you. A nice person will tell you what feels good - and often what you think you want to hear at that time - even if it doesn’t help you move past that situation.

A kind person supports you as you adapt, grow, and evolve. They remind you that evolving as a human being isn’t something to be ashamed of. That everything evolves, and that’s life’s greatest accomplishment and reward. A nice person likes the version of you they know and wants you to keep that version, even at the risk of losing your place in the future. They are trying to shield you from the pain that comes from evolving - the experience of failing, learning, and improving into something new.

[…]

And when you experience pain, a kind person helps you see the progress that can come from the pain. They are gentle but truthful with their feedback. They nudge you to go to the pain instead of running from it. They support you as you note what the pain is like, how it makes you feel, and over time, what you will do about it. A nice person doesn’t want to ‘kill the vibe’ and wants you to be comfortable. To them, nothing screams discomfort like pain. They may tell you not to think about the pain, and it will ‘disappear’.

A kind person sits with you as you navigate a tough situation. If they know you can build the skills to handle it, they don’t try to ‘save’ you by removing the situation. Instead, they support you as you find the strength and resources that the situation requires. A nice person can’t stand you going through something that tough, so they jump in to save you. What the nice person forgets is that they are robbing you of the strength you need to deal with setbacks, the will to adapt and be resilient, and the reminder of the great things you can accomplish regardless of the situation.

A kind person reminds you about your internal locus of control. They remind you of your role in the outcome you are experiencing, and if you are wise, you’ll take absolute responsibility and hold yourself accountable. From the place of accountability, you can see clearly what you need to do. A nice person gives you reasons why what you are experiencing isn’t really your fault, and how you can blame it on the government, the economy, and anything else but you. They understand your excuses. They know you are a good person, and life isn’t just fair to you.

[…]

When you ask for feedback, the kind person will be warm and constructive in their feedback. But they will hold nothing back. They understand that the process of asking for feedback means you trust them enough for them to tell you the truth as they see it, even if it may bruise your ego. The nice person doesn’t want to hurt your feelings, they also will give you warm feedback. But just the good one. They don’t see it as their responsibility to tell you the ‘bad’ part. They imagine you’ll eventually hear it - maybe from the market, from those you serve, or from life.

If you have to choose between being nice and kind, the latter is a better option. The ultimate responsibility we all have is to be kind.

Peace,

SG